Dedication at front of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, “To Albert Schweitzer who said, ‘Man has lost the capacity to foresee and to forestall. He will end by destroying the earth.’”

In 1962, Velsicol sought to block publication of Silent Spring.

Three Lessons:

The human health and environmental problems arising from the operation of Michigan Chemical/Velsicol Chemical in St. Louis offer us three general lessons that should be learned far beyond the Pine River watershed.

Overview

The general lessons can be broken down into three broad areas:

1. Respecting the Precautionary Principle

2. Practicing Responsible Economics

3. Becoming Good Ancestors

Respecting the PRECAUTIONARY PRINCIPLE

Beginning with the concern with the human health consequences of the PBB accident, the community has repeatedly benefitted from the work and thinking of human health experts guided by the Precautionary Principle. What do we mean by those words? Briefly the Precautionary Principle means: caution should be followed in the introduction of new products or methods until the long-term impact on human health or the environment is known.

The community’s first contact with a modern advocate of the Precautionary Principle was when Dr. Irving Selikoff was asked to guide assessing the impact of the PBB accident on human health. At the same time, Tony Mazzocchi, of the Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers (OCAW) union that represented workers at the Michigan Chemical/Velsicol plant, was asked by local union leaders for help. A friend of Dr. Selikoff, Mr. Mazzocchi was another advocate of precaution. He and Dr. Selikoff often are identified as the “fathers” of occupational health policy in the U.S.

These leaders of the human health response to the PBB accident were not the first to be concerned with controlling the health risks of occupational danger. Long-ago, the brilliant Italian physician, Bernardino Ramazzini, who lived from 1623 until 1714, identified occupational health problems and called for the Precautionary Principle.

Bernardino Ramazzini

A few years after the PBB accident, Dr. Irving Selikoff joined with Dr. Cesare Maltoni of the University of Bologna in Italy to form the Collegium Ramazzini, bringing together world experts on occupational disease and the need for the Precautionary Principle. Several other experts who have become involved with helping us understand the human health consequences of exposures to Michigan Chemical/Velsicol contaminants are members of the Collegium: Dr. Chris De Rosa, who delivered the keynote address at the Kenaga International DDT Conference and Dr. Brenda Eskenazi, the lead author of “The Pine River Statement” published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

When Dr. De Rosa delivered his address at the Kenaga Conference, he began with a reference to the wisdom of Bernardino Ramazzini. If nothing else is taken from the lessons of the PBB accident, it should be to expect the precautionary principle to be applied to all new products and processes of production. Dr. De Rosa also urged us to pay attention to the meetings, usually annually of the Collegium. As the Collegium says on its website: “The mission of the Collegium Ramazzini is to increase scientific knowledge of the environmental and occupational causes of disease and to transmit this knowledge to decision-makers, the media and the global public to protect public health, prevent disease and save lives. The Collegium Ramazzini is independent of commercial interests. It advances scientifically based solutions to global problems in occupational and environmental health.”

Dr. Christopher De Rosa was the Director for Toxicology and Risk Analysis for the National Center for Environmental Health/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Dr. Brenda Eskenazi is the Brian and Jennifer Maxwell Endowed Chair in Public Health and Director of the Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health.

Dr. Eugene Kenaga, for whom the Pine River Task Force named the 2008 International DDT Conference, which he wanted us to hold, was a long-time employee of Dow Chemical and as a young chemist during World War II in the South Pacific helped develop the use of DDT to fight malaria. He believed in cautious use of DDT. He later founded the Society for Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, which co-sponsored the DDT Conference. [See the article by Gene Kenaga describing pesticide regulation efforts, here copied with a 1945 New Yorker story warning of DDT’s dangers]

In January 1998, the same month the Pine River Task Force was founded in St. Louis, Carolyn Raffensperger and the Science and Environmental Helth Network helped organize the Wingspread Conference on the Precautionary Principle. Later, Raffensperger co-edited Precautionary Tools fo Reshaping Environmental Policy (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2006).

Here is the text of the Wingspread Statement on the Precautionary Principle, Jan. 1998

“When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and

effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the

burden of proof. The process of applying the precautionary principle must be open, informed and democratic and must include potentially

affected parties. It must also involve an examination of the full range of alternatives, including no action.”

Anthony ‘Tony’ Mazzocchi was an elected officer of the Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers Union (the Union of workers at Michigan Chemical), now part of the United Steelworkers. President Richard Nixon credited Tony with having gotten the Occupational Safety and Health Act enacted in 1970. He has been called the “Rachel Carson of the American Workplace.” He is portrayed in the film Silkwood.

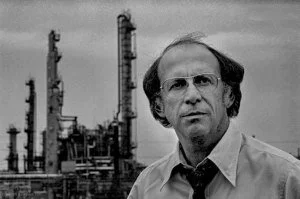

Tony Mazzocchi at Work

Dr. Irving Selikoff was the long-term occupational health pioneer. He served as the Director of the Environmental and Occupational Health Division of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. After his death, it was renamed the Selikoff Centers for Occupational Health. Dr. Michele Marcus, who leads the PBB Registry team at Emory University worked for and with Dr. Selikoff.

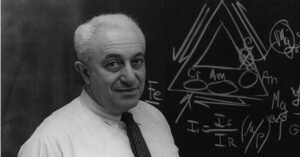

Dr. Selikoff

2. Practicing RESPONSIBLE ECONOMICS

A second set of lessons from the experience with remediation of the local environment and restoration of public health apply to economics. As with the Ramazzini legacy, an international organization has grown up to further economic learning from these experiences – the International Society for Ecological Economics (ISEE). The U.S. section of the ISEE has published work on the economics of the Pine River region’s remediation.

See pp. 119-134 on Michigan Chemical

The ISEE was founded by Herman Daly, a former World Bank economist and professor at a number of leading U.S. universities, and author of pioneering work on “steady-state economics.” [On steady-state economics go to the Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy - CASSE website.] The ISEE, especially in Michigan has been guided by the work of Nobel Prize winning economist Eleanor Ostrom on the protection of the ‘commons.” One recent treatment of Ostrom’s life and thought is Erik Nordman’s The Uncommon Knowledge of Elinor Ostrom: Essential Leon for Collective Action (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2021).

Kate Raworth, at Oxford University has also contributed much insight into problems such as those in the Pine River watershed with her concept of “donut economics.”

Kate Raworth’s Book

Of special relevance to the Pine River experience has been Eleanor Ostrom’s eight “design principles” for producing stable use of common resources, such as the water of the river, the lands shared in the community for housing and the air. More important than helping one local community, the experience of St. Louis confirm the accuracy of what Dr. Ostrom identified. To see a complete explanation of her principles, please read her Governing the Commons (New York, Cambridge University Press, 1990). Ostrom was the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences (in 2009).

Governing the Commons

We know that the behavior of Michigan Chemical/Velsicol was economically foolish from the long-term perspective of the community. The company never paid in wages and taxes, even when adjusted for inflation, a sum equal to the Superfund clean-up costs. And those cost computations do not factor in the ‘costs’ of human health consequences experienced by people exposed to the contaminants, especially PBB introduced into the food chain or DDT and other chemicals to which people in the region were exposed through, air, water and soil contamination. How can we possibly estimate the ‘costs’ of a lost child or a shortened life or one made more unpleasant due to a health consequence of exposure. Added to those missing ‘economic’ measures are the losses to the natural world, which can also have direct impacts on humans. Perhaps the easiest way to understand the negative economic impact of Michigan Chemical/ Velsicol is the fact that the company only operated for 42 years in the watershed (1936-1978). The clean-up has now lasted longer than the operation and remediating the environmental and human health legacy will be continuing for many years into the future. Clean-up in St. Louis already exceeds 42 years!

When the Pine River Task Force succeeded in its bankruptcy claim against upriver Oxford Automotive, the bankruptcy court award was based on an estimate of the lost monetary benefit from being able to carry on recreational fishing in the river. Similarly, the residents of the region have lost something of incalculable value in not being able to freely use other natural resources.

As has been argued by globally respected economists such as Daly, Ostrom and Raworth, we urgently need a new way of measuring and regulating the economic impacts of irresponsibility such as that exemplified by Michigan Chemical. Since it appears some of the chemicals introduced into the environment by the firm can have genetic impacts on future generations of exposed people, the foolishness of economic assumptions that allowed the firm to operate as it did between 1936 and 1978 becomes crystal clear.

3. Becoming (and remaining) GOOD ANCESTORS

A core lesson in the watershed is that claims, such as, ‘If they knew it was bad, they wouldn’t have done it,’ are a full distortion of the truth. As soon as Michigan Chemical announced plans to open, without waste processing beyond river dumping, downriver people complained. Perhaps worse, the contamination took place when peer reviewed scientific studies warned of the dangers of exposures to the products and processes of the companies. In the section of the website, we provide copies of SOME of the many examples of complaints, media reports, and scientific studies. Many more can be found if you check the books on the PBB accident identified on our resource page.

A recent book, Roman Krznaric’s The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short Term World (New York: The Experiment, 2020) reviews the long history of taking responsibility for the world we leave to our descendants. When we held the c0nference focused on the 50th anniversary of the PBB mistake, Joseph Sowmick of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe reminded us of the indigenous consciousness of the impact of actions today down seven generations. Obviously, the experience in the Pine River does ntreflect the slightest concern with intergenerational responsibility. In fact, in 2023, during summer work by EPA to clean the watershed, the Pine River next to the clean-up sites often was covered by stinking biproducts of the dumping of too much animal waste into the river in farms upriver. Observers had no delay in responding, “When will they learn?” . We should make reading Krznaric’s book mandatory for all residents of the watershed!

Roman Krznaric followed up on The Good Ancestor with History for Tomorrow: Inspiration from the Past for the Future of Humanity. History for Tomorrow appeared first in the United Kingdom in 2024 and then in the U.S. in 2025. As with The Good Ancestor, this book helps us understand the importance of learning from the environmental and related human health experiences along the Pine River. Our local experience, especially the long term, multi-generational impact from the PBB accident makes crystal clear that all people, not just those along the Pine River, need to learn from the lessons we identify here. Please check out Roman Krznaric’s books!

In addition to the poor ancestor problem in St. Louis, there is clear evidence in per capita income and average house value that St. Louis is an environmental justice community. Beginning in 1997, when US EPA returned to the community and launched the emergency removal action focused on DDT in Pine River sediments, the community has become an example of the many environmental justice communities in Michigan. Soon after the Pine River Task Force, incorporated in January 1998, through Alma College it began contact with leaders in the environmental justice movement. Twice, we had Robert Bullard the founder of the environmental justice movement do major presentations at the college. We read his pioneering Dumping in Dixie, and then became familiar with the ‘Michigan Group’ in the environmental justice movement led by Bunyan Bryant at the University of Michigan.

Repeatedly since that time, the Task Force has been involved in wider environmental justice concerns beyond our watershed. When the Task Force in 2002 pressured the Us Department of Justice to hold a public hearing in St, Louis on the proposed Fruit of the Loom bankruptcy settlement, the Task Force reached out to our friends in the largely minority community around the Velsicol plant in Memphis, Tennessee. Members of that community group were able to attend the hearing in St. Louis and then pressured US DOJ to hold a follow-up hearing in their community. Since the Fruit of the Loom settlement distributed bankruptcy funds in both St. Louis and Memphis and other communities in both Michigan and Tennessee we battled across stateliness to empower potential victims of environmental racism.

At other times, continuing until the recent PFAS concerns, the Task Force has partnered with other environmental justice communities across the state, especially in Detroit and Flint, in sharing knowledge and concerns. We have become aware that much as ‘bad ancestors’ have failed to consider the consequences for future generations of short-term profiting from pollution or sale of dangerous products, environmental injustice is a temptation for the politically powerful to pressure policy makers into irresponsible environmental behavior threatening poor and less influential communities. Consequently, the poor bear a disproportionate share of the human health and environmental costs of contamination. Limited common resources that should be used in a sustainable way so they remain for all today and in future generations become unusable, as the Pine River below St. Louis, as they are used for short-tun profit of a few.

To begin understanding these issues, we urge reading of Robert Bullard’s Dumping in Dixie (Boulder: Westview Press, 1990). Because Velsicol operated a number of plants in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Texas, that book is especially relevant, even though its focus is not on our community.

There also is the issue of the upper river or upwind polluter. St. Louis is only the second municipality of any size on the Pine River. Alma, four miles upriver has had a long history of industrial contamination. Elsewhere we reference the pollution issues related to the Total (Leonard Refinery in Alma and run-off from Oxford Automotive (Lobdell Mfg.), a metal plating firm. Velsicol (Michigan Chemical) added grievously to the pollution burden in the Pine River. About thirty-five miles downstream, the Alma-St. Louis pollution began to impact much larger communities such as Midland, Saginaw and Bay City, before entering into, Saginaw Bay and then Lake Huron and then threatening the waters of Canada as well as the U.S. until the St. Lawrence River dumps into the ocean. Accordingly, the Task Force has had multiple contacts with the International Joint Commission (the Canadian-U.S. agency responsible for the Great Lakes). On several occasions, we have invited health and environmental experts associated with the IJC to St. Louis ush as at the Intergeneration Risk Conference in 2016.

As many involved in the Breckenridge Cancer Cluster know, those health problems have been blamed by some on likely exposure to air emissions from Velsicol. The prevailing wind patterns over St. Louis, on most days would carry contaminants from Michigan Chemical over Breckenridge a few miles down wind.

Related to up river and upwind pollution, we would urge reading of books such as Benjamin Kline’s First Along the River (Lanhsm, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2022). The fifth edition gives some attention to the PBB crisis.

Pine River Experience with “Bad Ancestors,“ environmental injustice and the up-river/ upwind syndrom:

While many local residents and local, state and national officials have worked to control the regions contamination for the good of future generations, we have been plagued by many “bad ancestors” focused on short-term profits at the expense of future generations. It is important, therefore, to understand the long-term struggles against pollution.

Below we not only show private expressions of criticisms of dead fish or river smells. We include a variety of assessments from public officials and government expert as early as the mid-1930s. We begin with a link to a resolution unanimously adopted by the Saginaw City Council regarding Pine River contamination from St. Louis.

That led to an investigation of problems on the Pine River by the only institution at the time capable of studying ecosystem degradation – The University of Michigan.

Again, we know in 1941, 121 citizens in St. Louis, the community seemingly benefitting from the chemical plant jobs, complained of harm to the river.

Image of Front Page of Local Newspaper in 1941 about citizen complaints

Throughout the pre-PBB Accident era (1935-1973), repeatedly state environmental agencies documented contamination in the Pine River. For example, in 1955, the Michigan Stream Control Commission reported on river contamination.

Again from 1967 until 1970 the Michigan Water Resources Commission conducted a river assessment with much information on Michigan Chemical contamination (copied in 3 parts).

Mi Water Res Com Pine River 1967-70 title page

Mi Water Res Com Pine River 1967-70 pp to 8

Mi Water Res Com Pine River 1967-70 all other

As part of the larger study, the Michigan Water Resources Commission in 1967, produced a report on Michigan Chemical’s impact on the watershed.

Mi Water Resources Com 1967 on Michigan Chemical

The consequence of all of these reports is to prove there is overwhelming evidence the problems of Michigan Chemical were known and the public wanted action.

Ignored Human Health Concerns:

Knowledge of the dangers of the products of Michigan Chemical. Velsicol Chemical were documented and publicized. One reason no action was taken in response to the known risks of the companies’ products was that they and their allies fought back with legal threats and lobbying at the highest levels.

As World War II ended multiple accounts appeared I the popular press of problems with DDT. In 1945, the New Yorker, a major popular magazine, one of whose editors was E.B. White (of Charlotte’s Web fame) ran a story on DDT’s danger. [See the included later link to a story about Gene Kenaga, later a Pine River Task Force member who long confronted DDT lobbyists.]

New Yorker May 26 1945 & Kenaga review of pesticide regulation

The year after The New Yorker story, another popular magazine, The New Republic ran a story about DDT’s dangers.

New Republic March 25, 1946 on DDT

These accounts in the popular press were supported by peer reviewed studies published in scholarly journals. For example, The Journal of Pharmacology, published this study in 1947. [Peer review means before an article is published, it is reviewed by other experts who are not told who wrote the report and so make a neutral assessment of the article’s accuracy.]

Two years later, the American Medical Association’s Archives of Pathology, another peer reviewed scientific journal, published a study in 1949 showing the impact of DDT on dogs, but with obvious worry about the impact on human health. [Peer review means before an article is published, it is reviewed by other experts who are not told who wrote the report and so make a neutral assessment of the article’s accuracy.]

At Michigan State University (MSU), in the late 1950s and 1960s, ornithologist Dr. George Wallace quietly investigated studies of bird deaths after DDT spraying on-campus. After he testified about his findings, agricultural interests in the state sought to have him fired. See the description of what the university later admitted was harassment and an embarrassment to MSU. [NOTE: This George Wallace is not the former Governor of Alabama.]

Al these ignored warnings about DDT, and also a number of products of Velsicol, led to Rachel Carson writing Silent Spring, to be published in September 1962 by Houghton Mifflin, the old Boston publisher of quality books. It also was to be serialized in the summer of 1962 by E.B White’s New Yorker. Here are a variety of documents including letters from Velsicol’s attorneys threatening Houghton Mifflin with a liable suit if the book was published. The New Yorker received similar threats. In addition to these documents, if you watch the PBS American Experience documentary on Rachel Carson, there are discussions of the Velsicol threats with Paul Brooks, the former editor at Houghton Mifflin and friend of Rachel Carson. (some of these are poor quality images, originals at Rachel Carson Papers at Yale Univ. archives of this quality)

After Houghton Mifflin defied the threats and published Silent Spring, there was a campaign of pesticide producers to attack the book in reviews. The American Medical Association ran a negative review. Likewise, Chemical and Engineering News (CEN) attacked Carson. Here are copies of those reviews, but also a few letters to the editor of CEN defending Carson.

In addition, Velsicol and Shell Chemicals teamed up to pay for a ghost-written book, supposedly by Jamie Whitten, the long-serving Chair of the U.S. House of Representatives Agriculture Committee, That We May Live. To assure it was a ‘best seller’, the two companies not only paid for its publication but bought eh copies produced and donated them to politicians and public libraries – pioneering a strategy later used by many public policy campaigns. Here is a picture of the cover of That We May Live. Please don’t buy a used copy. It is propaganda.

If you want more information on disinformation campaigns such as this, check out Naomi Oeskes and Erik Conway, Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010). You can check their website for more media: Merchants of Doubt – How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming

Please learn these lessons and teach them to future generations! If you had exposure or other involvement with PBB, we would like to hear your stories. Please check out the Michigan PBB Registry and the PBB Oral History Project.